July 15th-July 22nd, 2022

Do Flavonoids Have a Future Role in the Treatment of Bladder Cancer?

The flavonoid cannflavin A in combination with phytocannabinoids may be a better treatment strategy compared to chemotherapeutic agents, a new study suggests.

Bladder cancer is a type of cancer that begins in the cells of the bladder. It is estimated to account for 500 000 new cases and 200 000 deaths worldwide, with the US accounting for 80 00 new cases and 17 000 deaths each year. [1],[2] The most common type of bladder cancer is transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), occurring in approximately 90% of bladder cancer cases. [3] Established risk factors include older age, chronic bladder infection/irritation, personal or family history of bladder cancer, and cigarette smoking. [4] Patients with bladder cancer most likely presents with painless hematuria (blood in the urine), irritative symptoms (e.g., urge incontinence), or obstructive symptoms (e.g., intermittent stream). [5]

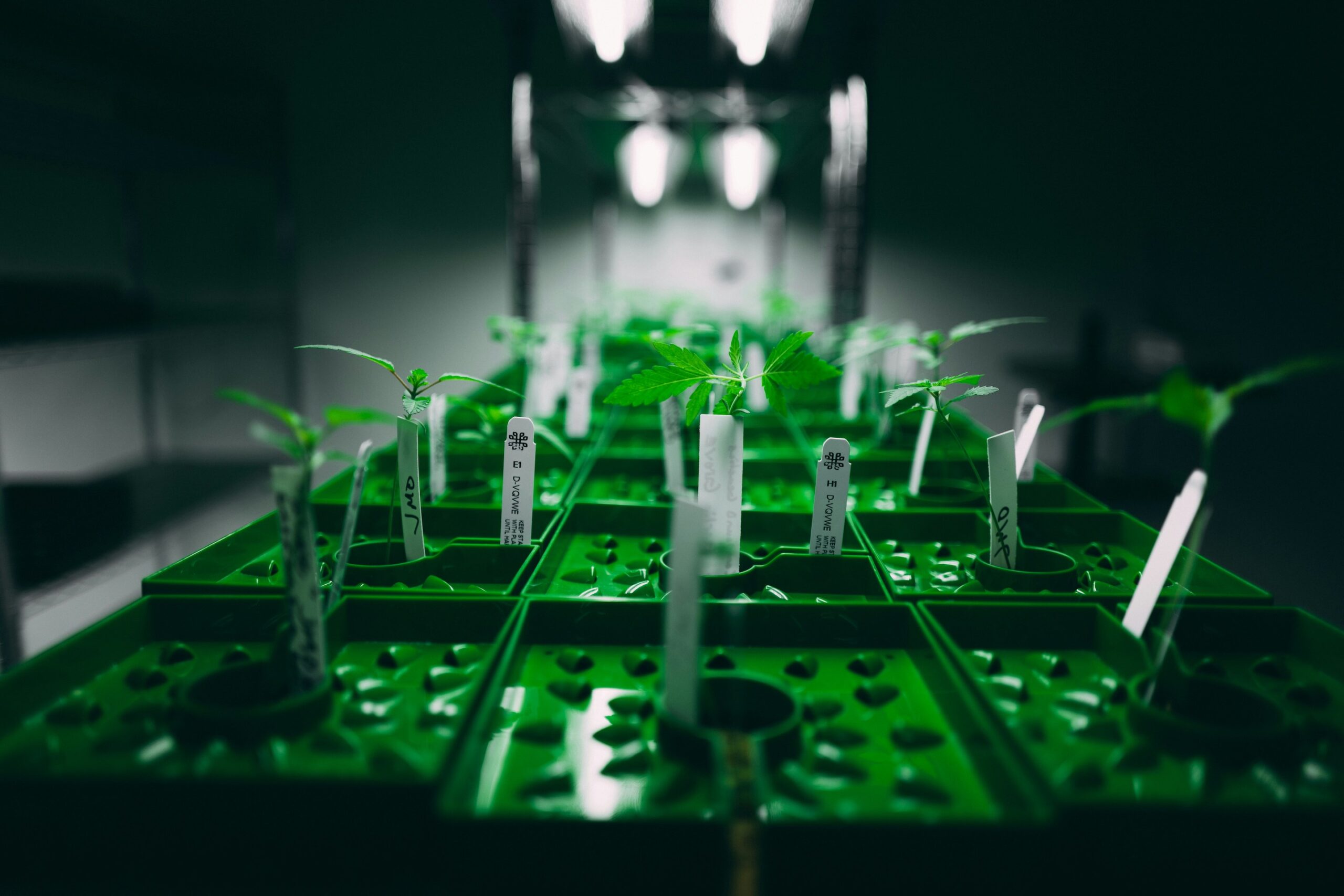

Despite the development of chemotherapy drugs has proven efficacious in improving patient’s survival, alternative regimens which may further ameliorate their outcomes are being considered. While smoking is a known risk for bladder cancer, it has suggested that cannabis consumption may reduce bladder cancer incidence. [6] In this way, compounds in the cannabis plant, most specifically the phytocannabinoids cannabidiol (CBD), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), and cannabichromene (CBC) may play roles in inhibiting tumor cell growth. [7] While the attention is focused on phytocannabinoids, the cannabis plant also contains terpenes and flavonoids, which are also associated with health benefits. There are about 20 flavonoids identified in the cannabis plant including cannflavins A, B, C, which may have anti-inflammatory properties. [8] However, little is known about their potential roles in treating bladder cancer.

A group of researchers from Dalhousie University in Canada aimed to evaluate the effects of cannflavin A alone or in synergy with two chemotherapeutic agents, gemcitabine, and cisplatin, or with cannabinoids using bladder cancer cell lines. [9] Using cytotoxicity and apoptosis assays, they found that the use of cannflavin A alone (at 100 mM) was able to decrease the % of cell viability similar to gemcitabine and cisplatin. Additionally, 2.5 mM of cannflavin A induced apoptosis, which was reversed in the presence of autophagy inhibitors. In terms of synergistic effects, results showed that it was more pronounced when cannflavin A was used in combination with cannabinoids such as CBD, Δ9-THC, CBC, and cannabivarin (CBV) rather than with chemotherapeutic agents.

The authors concluded: “Our results indicate that compounds from Cannabis sativa other than cannabinoids, like the flavonoid cannflavins A, can be cytotoxic to human bladder transitional carcinoma cells and that this compound can exert synergistic effects when combined with other agents….More investigation is needed to determine how cannabinoids and other compounds from cannabis like cannflavin A could be used therapeutically in the treatment of cancers and whether they could be used similarly to cannflavins B, alone, or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents.”

The Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Acts (CAOA) In Hope to Decriminalize Cannabis

The bill would implement new cannabis regulations including changes in cannabis tax policy, increase research funds, criminal justice reforms, and testing for federal workers, with the hope to reverse harm by the War of Drugs.

On July 21st, 2022, the U.S Senate introduced the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Acts (CAOA) bill with the goal to decriminalize cannabis at the federal level (a year after a draft was discussed), thanks to a combined effort from U.S Senators Ron Wyden (Oregon), Cory Booker (New Jersey), and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (NY). Overall, the bill would implement new regulations around cannabis tax policy, additional research funds, removing testing for federal workers (in most cases), criminal justice reform, and increase the permissible tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) levels from 0.3% to 0.7%. [10]

“The Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act will be a catalyst for change by removing cannabis from the federal list of controlled substances, protecting public health and safety, and expunging the criminal records of those with low-level cannabis offenses, providing millions with a new lease on life. A majority of Americans now support legalizing cannabis, and Congress must act by working to end decades of over-criminalization. It is time to end the federal prohibition on cannabis.”, said Schumer. [11]

To pass, the bill needs to receive support from all Senate Democrats and 10 Republicans.

Iron, Cannabinoid Receptor 2 (CB2R) & Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type-1 (TRPV1) in Regulating Osteoclast Activity in Childhood Cancer Survivors (CCS)

Understanding the relationship between these three components may help counteract osteoclast (OCs) overactivity and improve quality of life in CCS individuals.

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) population are a group of young individuals who, as their name suggests, survived cancer. However, curative therapies can interfere with the normal aging process, which can lead to impairments of vital organs, with tissues metabolically active such as bones mostly being affected. [12],[13],[14]As such, CCS individuals are more prone to develop low bone mineral density (BMD) due to the use of leukemia drugs which can induce a decrease of BMD.[15],[16] Moreover, it is known that iron metabolism and inflammation can regulate osteoclast (OCs) activity, a class of bone cells that break down bone tissue. [17]

Cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R), mostly expressed in the peripheral nervous system and immune system, and the transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 (TRPV1) are potential attractive targets for bone diseases and osteoporosis, a condition in which bones become weak and brittle. On one hand, CB2R stimulation inhibits OCs activity, while TRPV1 activation is stimulatory. [18],[19]

A study by Rossi et al. published in PLoS One aimed to investigate the OCs activity in CCS and determine the effects of CB2R and TRPV1 stimulation with an iron chelator (compound that counteract OCs activity), on OCs activity and iron metabolism.[20] Using a group of 40 subjects (20 healthy controls and 20 CCS), the authors first showed that the CSS samples had a greater expression of two important OCs markers, confirming OCs hyperactivation. Secondly, an increase in the pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and in iron was recorded in the CSS group, which was reduced after the addition of the iron chelator. Finally, CB2R and TRPV1 stimulation with their respective agonists led to a significant decrease of OCs biomarkers as well as changes in iron metabolism, suggesting that these receptors are potential key biomarkers one may need to considerate when addressing bone damage in CCS patients.

The authors concluded: “Our study demonstrates, for the first time, an osteoclast hyper activation in CCS and suggest a crucial role for iron in its development… In the future in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to validate our data and to translate them to the clinical practice.”

Synthetic Cannabinoids & Oral and Pancreatic Tumors

The synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212–2 was able to inhibit tumor cell proliferation and induced cell death of oral and pancreatic tumor cells, a new study reports.

The use of cannabinoid-based drugs to improve side effects associated with radio and chemotherapy such as reducing nausea and stimulating appetite are gaining interest among cancer patients. As of July 2022, the FDA has approved a small number of synthetic cannabinoids that mimic the structure and activity of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), indicated for the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy, including Syndros® (dronabinol-based), Marinol® (dronabinol-based), and Cesamet® (nabilone-based). [21],[22],[23] These synthetic cannabinoids are different than phytocannabinoids (cannabinoid molecules produced from the cannabis plant) and endocannabinoids (cannabinoid molecules derived naturally from our bodies), as they are artificially produced by scientists to mimic the effects of specific cannabinoids.

WIN 55,212-2, a potent cannabinoid receptor agonist, is a synthetic cannabinoid that has been reported to exhibit anti-tumor effects in a wide range of tumor types such as renal cell carcinoma, breast, or lung cancers. [24][25][26][27] However, its effects on differentiated vs stem-like tumor cells are yet to be determined.

Using carcinoma cells from cancer patients with tongue tumor and human pancreatic cancer cell lines, Ko et al. demonstrated that WIN 55,212-2 was able to inhibit cell proliferation and induced cell death in oral tumor cells, along with a decrease in specific cell surface expression markers that are typically expressed in tumors. [28]Additionally, they showed that this surface expression of cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) but not cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) was higher on differentiated and stem-like/poorly differentiated tumor cells.

The authors concluded: “Overall, our studies indicate that synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 has greater killing effect on CSCs/poorly differentiated tumor cells than well-differentiated tumor cells and may have potential to be used in patients with aggressive and metastatic tumors… Our future studies will focus on delineation of underlying mechanisms which govern the function of WIN55,212–2 in the lysis of stem-like tumors, and its potential role in activation of NK cell function.”

References:

[1] Richters A, Aben KKH, Kiemeney L. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer: an update. World J Urol 2020;38(8):1895-1904. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-019-02984-4.

[2] Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69(1):7-34. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21551.

[3] Pons F, Orsola A, Morote J, Bellmunt J. Variant forms of bladder cancer: basic considerations on treatment approaches. Curr Oncol Rep 2011;13(3):216-21. DOI: 10.1007/s11912-011-0161-4.

[4] Lenis AT, Lec PM, Chamie K, Mshs MD. Bladder Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2020;324(19):1980-1991. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.17598.

[5] DeGeorge KC, Holt HR, Hodges SC. Bladder Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician 2017;96(8):507-514. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29094888).

[6] Thomas AA, Wallner LP, Quinn VP, et al. Association between cannabis use and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the California Men’s Health Study. Urology 2015;85(2):388-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.060.

[7] Anis O, Vinayaka AC, Shalev N, et al. Cannabis-Derived Compounds Cannabichromene and Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Interact and Exhibit Cytotoxic Activity against Urothelial Cell Carcinoma Correlated with Inhibition of Cell Migration and Cytoskeleton Organization. Molecules 2021;26(2). DOI: 10.3390/molecules26020465.

[8] Erridge S, Mangal N, Salazar O, Pacchetti B, Sodergren MH. Cannflavins – From plant to patient: A scoping review. Fitoterapia 2020;146:104712. DOI: 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104712.

[9] Tomko AM, Whynot EG, Dupré DJ. Anti-cancer properties of cannflavin A and potential synergistic effects with gemcitabine, cisplatin, and cannabinoids in bladder cancer. J Cannabis Res. 2022 Jul 22;4(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s42238-022-00151-y. PMID: 35869542.

[10] https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/caoa_final_introduction.pdf, assessed on July 22nd, 2022

[11] https://www.booker.senate.gov/news/press/booker-schumer-wyden-introduce-cannabis-administration-and-opportunity-act, assessed on July 22nd, 2022

[12] Chemaitilly W, Cohen LE, Mostoufi-Moab S, et al. Endocrine Late Effects in Childhood Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(21):2153-2159. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3268.

[13] Landier W, Skinner R, Wallace WH, et al. Surveillance for Late Effects in Childhood Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(21):2216-2222. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.0180.

[14] Leonardi GC, Accardi G, Monastero R, Nicoletti F, Libra M. Ageing: from inflammation to cancer. Immun Ageing 2018;15:1. DOI: 10.1186/s12979-017-0112-5.

[15] Jin HY, Lee JA. Low bone mineral density in children and adolescents with cancer. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2020;25(3):137-144. DOI: 10.6065/apem.2040060.030.

[16] Mandel K, Atkinson S, Barr RD, Pencharz P. Skeletal morbidity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2004;22(7):1215-21. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.199.

[17] Camaschella C, Nai A, Silvestri L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica 2020;105(2):260-272. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2019.232124.

[18] Bab I, Ofek O, Tam J, Rehnelt J, Zimmer A. Endocannabinoids and the regulation of bone metabolism. J Neuroendocrinol 2008;20 Suppl 1:69-74. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01675.x.

[19] Ofek O, Karsak M, Leclerc N, et al. Peripheral cannabinoid receptor, CB2, regulates bone mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103(3):696-701. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0504187103.

[20] Rossi F, Tortora C, Di Martino M, et al. Alteration of osteoclast activity in childhood cancer survivors: Role of iron and of CB2/TRPV1 receptors. PLoS One 2022;17(7):e0271730. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271730.

[21]https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2016/205525Orig1s000TOC.cfm), assessed on July 22nd, 2022

[22] https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/018651s029lbl.pdf, assessed on July 22nd, 2022

[23] (https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process, assessed on July 22nd, 2022

[24] https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/win-55212-2#:~:text=WIN%2055212%2D2%20is%20a,agent%20and%20an%20apoptosis%20inhibitor. assessed on July 22nd, 2022

[25] Khan MI, Sobocinska AA, Brodaczewska KK, et al. Involvement of the CB2 cannabinoid receptor in cell growth inhibition and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest via the cannabinoid agonist WIN 55,212-2 in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2018;18(1):583. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-018-4496-1.

[26] Qamri Z, Preet A, Nasser MW, et al. Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit tumor growth and metastasis of breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2009;8(11):3117-29. DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0448.

[27] Preet A, Qamri Z, Nasser MW, et al. Cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, as novel targets for inhibition of non-small cell lung cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(1):65-75. DOI: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0181.

[28] Ko M-W, Breznik B, Senjor E, Jewett A. Synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212–2 inhibits growth and induces cell death of oral and pancreatic stem-like/poorly differentiated tumor cells. Advances in Cancer Biology – Metastasis 2022;5:100043. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adcanc.2022.100043.